Will's Story

About Will

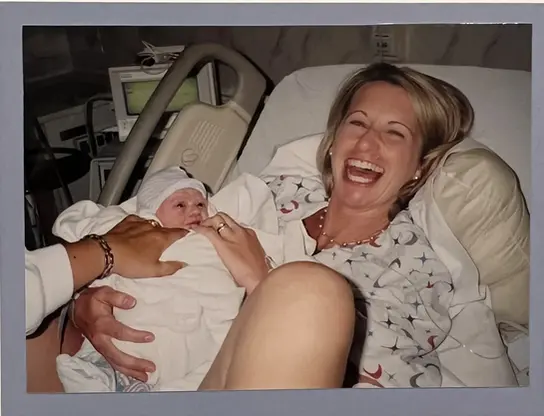

William Cole Carpenter’s life was brief but blazed with extraordinary courage, love, and light.

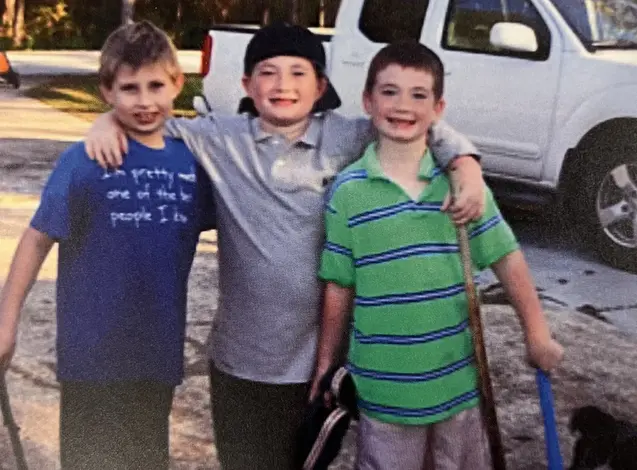

At just 18, Will stepped onto the campus of the University of Central Florida to chase his dreams in Electrical Engineering. He was a record-breaking swimmer, a fierce competitive fisherman, and a devoted Jacksonville Jaguars fan whose joy lit up every room. His heart was as big as his smile — always ready to cheer someone on, make them laugh, or lend a helping hand.

In December 2021, what seemed like a stubborn sinus infection turned out to be Alveolar Rhabdomyosarcoma, a rare and aggressive cancer. Will faced months of brutal chemotherapy and radiation, yet never let it steal his hope. Even as the disease returned and spread relentlessly through his body, he fought on — driven by an unbreakable will to live, to love, and to share moments with those he cherished.

On January 31, 2023, at just 19 years old, Will’s brave fight came to an end. In his final moments, his family felt a deep, peaceful presence — a sense that his spirit was finally free from pain.

Through this foundation, Will’s light continues to shine. His story now fuels hope, compassion, and strength for countless others, reminding us all that even in our darkest moments, love and courage endure.

Will's Story

His name is William Cole Carpenter, and this is the story of the fight for his life.

In the fall of 2021, he had a Florida Bright Futures Scholarship and was a freshman at the University of Central Florida, majoring in Electrical Engineering. This beautiful child was a top swimmer and even broke two records at his high school. He was an avid competitive fisherman and was on the UCF Bass Fishing Team. He absolutely loved the Jacksonville Jaguars and could tell you all about each player.

In August, he moved into the dorms at UCF to start his freshman year. Around September, he started having sinus problems. There were rumors of mold in the dorms, and he always had allergies, so I was treating the symptoms… Claritin D, Mucinex, Flonase, nasal rinses, etc. But he got no relief from any over-the-counter remedies or medications. I am a pharmacist; therefore, I know all the different ways to relieve the normal Florida sinus congestion. But nothing worked. The congestion got progressively worse on his left side, and a lymph node swelled up under his chin. I decided it was time for an antibiotic. The doctor’s visits started when he was home for the Thanksgiving holidays.

Over the next four weeks, there were multiple doctor visits and progressively stronger antibiotics in hopes of beating this “nasty sinus infection” concentrated on his left side. Once he was home for the Christmas holidays, he was experiencing some visual changes, trouble sleeping, numbness in his upper teeth, and another lymph node was swollen. This new lymph node was very large and on the left side. His doctor and I knew he needed some imaging done to see what was going on. It was now the end of December. I was desperately trying to get him better before Christmas break was over, and he had to go back to school. I couldn’t send him back to school sick, right?

The next step needed to be an ENT visit, but I knew that would take some time. Will and I were in his pediatrician’s office on Dec. 23, and she told me to take him to the UF Health ER in Gainesville. She said they had great ENTs that work in the ER, and this would be the fastest way to see a specialist and get a CT scan of his sinuses all at once. She tried to calm my increasing anxiety by reminding me of the mold rumor. She truly believed that it would turn out to be a fungal infection, polyp, or a mucus plug — something that needed to be lanced. Despite her reassurances, I could not shake this terrible feeling in the pit of my stomach. After leaving her office on Dec. 23, we went to the ER in Gainesville. Walking into an ER with the chief complaint of a lingering sinus infection put us in the waiting room for seven hours. Once we got a room, all the tests to rule out the cause of the lymph nodes started: mono, flu, COVID, strep throat… but everything was negative. Due to the size of the lymph nodes and the swelling around his left eye, imaging began.

By now, it was Christmas Eve. A few hours later, the ER doctor came in and looked at me with tears in her eyes. She said that this isn’t an infection. There is a large mass in his left sinus. She told me they weren’t sure what it was, but ENT was on their way down to the ER right now to take over the case. I stopped breathing. I couldn’t even process what she was telling me. What do you mean by a mass? This is a stubborn sinus infection, polyp, something that needed to be lanced… not a mass. What? ENT got there and ran a camera into that left sinus, and you could see the mass. It was terrible. It was taking up the whole left side. After more CT scans and an MRI, the ENT oncologist came in and talked to me. By this time, we had been there for 18 hours. I have never been so terrified in my life. He brought the computer in so he could show us the CT scans. You could see the tumor, and it was huge. It had more than likely only been there for 2–3 months, but had already filled up the entire left maxillary sinus. It was eroding the base of the brain stem and growing under and behind his eye. How can this be? The pathology lab was closed because it was Christmas Eve, so we couldn’t get a biopsy done until Monday. It was a very somber Christmas weekend. We prayed so hard that it wasn’t malignant, but I knew it was. I saw it. We were in a daze, just going through the motions until we could get the biopsy on Monday.

The ENT oncologist got him in first thing Monday morning to obtain the biopsy. He put it in as a stat order, so the biopsy results came back the next day. I heard what all parents are terrified of being told: Your child has cancer. There are no words to describe the feeling you have when hearing those words. You hear about children getting cancer, but how is this happening to your child? On December 28, 2021, my precious son was diagnosed with a rare, aggressive cancer called Alveolar Rhabdomyosarcoma FOX1/PAX3 Fusion Positive with regional lymph node involvement. Our world just stopped. He had a plan for his life, and he was on that path, but his future was now a question mark. The Rhabdomyosarcoma team contacted us right away and put him in the hospital that Wednesday morning. They explained that there was so much pressure on his eye that they had to start chemo immediately or he could lose it.

The next few days were a blur of CT scans, MRIs, PET scans, port placement, bone marrow biopsy, bone scan, etc. We were given a schedule for his treatment: a total of 67 weeks of high-dose chemotherapy consisting of five different medications (ARST 1431) with six weeks of proton radiation after the fifth cycle. Surgery was not an option due to the tumor’s location. One of the chemotherapy drugs would make him sterile, so he decided to freeze his sperm. At UF Health in Gainesville, he started chemotherapy on December 31, 2021 — New Year’s Eve. One week after our ER visit, he had been biopsied, diagnosed, and treatment had started. One week from us walking into that ER, thinking he had a lingering sinus infection, my baby was getting poison pumped into his body.

The next week, he had to make a medical withdrawal from the University of Central Florida. The first week in January, we moved him out of his dorm and back home. It was a sad day. But we had a plan, and he was ready to fight. Our family buckled down for what we thought was coming, and I started learning anything and everything I could about this cancer. We looked at this as just a pause in his life. There was a big, long book of his life, and this was only going to be a chapter in it.

Chemotherapy was brutal. He was in the infusion clinic every week and sometimes every day of the week. Some of the combinations were so toxic that he had to be hospitalized to receive them. He was sick, lost all his hair, and was weak, but he never lost his positivity. Our life was nothing but trips back and forth to Gainesville, bloodwork, watching counts, managing his horrific nausea and vomiting, and keeping on schedule with the many additional medications and injections prescribed to keep the chemo from killing him.

In March 2022, after the fifth cycle, he had his updated PET scan and MRI. The tumor had shrunk by half; the regional lymph node swelling was completely gone, and there was no evidence of disease progression. It was working! It was going to be okay, and I wasn’t going to lose my baby to this beast. He was beating it. I was able to breathe again. With great scans, it was time to start proton radiation at UF Proton Institute in Jacksonville.

The last week in March 2022, he started proton radiation every day for six weeks — radiation to his face and neck. The mask that he had to wear during radiation was one of the scariest things I’ve ever seen. He knew it was going to be tough and was ready to get through this next step. We moved into the Ronald McDonald House in Jacksonville for the duration of the radiation. His stepfather and I would tag out at 6 a.m. for one or the other of us to get to work. He continued his chemo at Nemours Children’s Hospital and was an inpatient at Wolfson’s Children’s Hospital for the combo that he had to be monitored with. With so much radiation to his face and neck, his skin became red and blistered — like a terrible sunburn. His mouth and esophagus were filled with ulcers, and it was extremely painful for him. He was prescribed morphine and hydrocodone to help with the pain and was on a liquid diet — all high-calorie, high-protein shakes and smoothies. He was losing weight and was so weak. Even being on a liquid diet, eating hurt him so much. We would spend so much time numbing his throat and esophagus so he could eat. He was so sick. I researched what his body needed and would make very specific smoothies for him to drink with the hopes he would absorb as much as he could before it came back up. Desperately trying to help his body fight this. My job was to keep the treatment from killing him.

After 31 radiation treatments, we returned home in May. Back to what was now our normal chemo regimen, and we were on week 20 of 67. He had lost so much weight and had such a hollow look to him. Since the radiation was to his face, his salivary glands were destroyed, and everything he put in his mouth turned to paste. As the weeks continued, we started to see the light at the end of the tunnel for frontline therapy. Getting to the maintenance phase, week 40 of the 67, of his chemotherapy protocol was a huge deal. The maintenance phase meant the chemo was slightly less toxic, and he wouldn’t be as sick. Will and I were thinking he could take a few classes at Florida Gateway College to start getting back on track. A huge bonus was that this college had a bass fishing team he could join. He was looking forward to getting his life back.

He had imaging done in August 2022, which was week 30. There was no evidence of the original tumor! It was completely gone! Plus, the lymph nodes had shrunk even more, and there was no evidence of disease anywhere else in his body. What a miracle! The only concern was a spot in his right shoulder that lit up slightly on the PET scan, but the oncologist thought he had bumped it or thrown his fishing rod too hard. Nothing to be concerned about. We would just watch it, and if it started hurting him, do an MRI.

At the end of September 2022, his shoulder started hurting. X-ray, MRI, and then a PET scan showed the spot in the right shoulder had declared itself. The cancer had metastasized to his right scapula. The only way to get a biopsy was to go in surgically, by drilling into his shoulder. An orthopedic oncologist and an integrative radiologist would work together to get a good sample. The results came back as rhabdomyosarcoma progression. This was devastating news. This meant that the tumor had mutated and was now resistant to the chemo that was being given. What? He had never stopped chemo. How could this beast become resistant to this extremely toxic chemo that had never stopped being pumped into him? I will never be able to portray the terror I felt at this moment. Was he going to beat it? How could this be? He was at week 37. Only three weeks away from entering the maintenance phase of treatment. He immediately started a new chemo regimen, and radiation was started to this new spot on his shoulder. His oncologist was optimistic about his prognosis. It was one contained site, and we had gotten it treated quickly. I tried so hard to believe what I was being told.

On October 20, 2022, an MRI was done to once again check on that original tumor, making sure that with the progression to the shoulder, this one was not regrowing. There was no evidence of the original tumor, but the radiologist saw a tumor in his spine. What? A tumor at the T3 vertebrae had already caused a compression fracture. This was another mutated progression that was resistant to both chemo regimens. Another PET scan was done. It showed that the original tumor, the original lymph nodes, and the right shoulder tumor were all gone. Nothing else in the body lit up, only the new tumor in his spine. Immediately, radiation was done to his spine, and he started his new chemo on November 7th. As we were running out of chemo options, they were becoming more and more toxic.

This new regimen was so harsh on his body. He was exhausted due to low blood counts and had no appetite. But he fought on, never once complaining about what he was going through. At the end of his first cycle with this new chemo regimen, it was Thanksgiving evening, November 24th. We visited my sister, and he went to bed early due to exhaustion. I checked on him later, and he was running a 102.6 fever. With a port, any fever over 100.4 could be indicative of an infection, and I knew he had to get to the hospital. Terrified and not at home, I called his oncologist. We were in Jacksonville, and they called Wolfson’s Children’s Hospital to advise them on Will’s situation and to have a bed waiting for him. With immunocompromised patients, the fear of sepsis from ports meant antibiotics were started immediately once entering the hospital. Blood work was done, and it showed WBC=0.4 and ANC=0. We were hospitalized for three days in Jacksonville. His ANC had to increase to 200 for him to be released. He was sweating so much that he was soaking the bed and had to have the sheets changed every 1–2 hours. He slept almost the whole time we were there.

Once home, his oncologist started him on daily methadone with other narcotics for breakthrough pain. He immediately had to start the second cycle of the chemo that had put him in the hospital. We had no other choice. Five days later, on December 2, he was back in the hospital. Uncontrollable, excruciating bone pain to the point where he couldn’t walk or sit up in bed. He was crying out from the pain, and the pain regimen he was on wasn’t giving him any relief. I had never seen him like this. He stayed in the hospital for seven days. He was on a morphine pump to get his pain under control. After two days, he was able to walk again and sit up in bed, still very shaky and weak. His pain and aching were attributed to the possibility of having the flu. There were many cases of the flu with immunocompromised patients in the hospital at that time, and the symptoms were exactly what Will presented with. I held on to this hope, but I knew this wasn’t the flu, and I think his oncologist knew that too. Once he was weaned off the morphine pump, he was discharged, and methadone was increased.

Once home, he had three good days, then went back to the hospital. Once again, for the pain that I couldn’t get controlled. This time it was not only his legs and back hurting, but also his other shoulder and chest. He was put back on the morphine pump to get him some relief. This was not the flu, and I think everyone in the room that day knew it. Imaging was scheduled for the next afternoon, but I wanted imaging now. Something was going on in his body, and we needed to know right now. I dug my heels in and refused to wait. Finally, they acquiesced, and his oncologist could get him in for an X-ray within the hour just to see if that showed anything before getting the PET and MRI moved up. The X-ray showed a new tumor on the left shoulder. After this terrible news, he was sent to get a bone scan that same day. The bone scan showed that the disease had infiltrated his bone marrow, and every bone in his body was full of tumors. Most were concentrated in his spine, sternum, hips, and knees. How could this be? The next day, he had the PET scan, and his entire body lit up with cancer. It was hard to comprehend the magnitude of what was happening. Our family was in complete shock. His body scans were clear two months ago. In that amount of time, despite never stopping chemo, this cancer had managed to take over his entire body. This is why he was in so much pain. He now has bone cancer, which is known to be the most painful cancer there is. My poor baby.

Will and I never lost focus, though. The PET scan showed it had spread throughout his marrow but wasn’t in his brain or organs. Will and I took that as a positive. We were faced with some hard decisions. At this point, do we continue chemo? The choices that were left were so very toxic and caused so many terrible side effects. The oncologist was looking at us with pity and was asking him what his goals were from here. Goals? The goal was to get this cancer under control. What did they think his goals were? Why were they asking this question? Why couldn’t they figure this out? And the looks of pity—Will and I hated those looks. I finally got Will to agree to a G-tube, and it was put in on December 27th. Maintaining his weight was such a struggle, and it was only going to get worse. This way, I could feed him what he needed and not disturb him. We were in and out of the hospital due to pain control. His oncology team decided to put him on Hospice home care. They could come to us and change pain medications without me having to bring him to the hospital. Although he and I did not like that word, we knew this would be the best. He and I decided on an oral chemotherapy regimen that would cause GI bleeding, severe mucositis, and crashing blood counts. With the G-tube, I didn’t have to feed him orally; therefore, we felt like that would be the best option.

My sister gave updates because I couldn’t anymore. I just didn’t have it in me. A well-known author, Sean Deitrich, saw his story and wrote an article about him. He asked people to pray for a miracle and send messages of encouragement and love to him. A P.O. Box was listed for anyone who would like to send letters and cards. The response was overwhelming. He started receiving thousands of cards from across the U.S. and even other countries. Whole schools drew pictures for him; people sent him cards, notes, and his favorite sports teams sent him merchandise and personal letters of encouragement. So much love for this one child trying to survive.

Our family knew this would be the last Christmas he would be with us. But none of us said it out loud. That Christmas, we took more photos than ever before, and I made sure to do all the traditional things that we did when they were kids. For the first time since mine and his dad’s divorce, both sides of the family, including aunts, uncles, and cousins, all came together. All because of the love we had for this child. We all wanted to soak up every moment we had left with him.

Starting with his first progression, I had gotten second, third, and fourth opinions from sarcoma specialists throughout the U.S. Being such a rare cancer, most of these doctors knew each other and were in communication with our oncologist to decide the best plan for treating Will’s cancer. But now, no one had any advice other than just picking one of what is called “salvage chemos.” After the news that it was moving like a freight train through his body, I also immersed myself in understanding Eastern Medicine. I felt like I had trusted Western Medicine for far too long, and it seemed to be feeding the cancer. I was working with an Integrative Oncologist from Oregon and a Naturopathic Oncologist in Thailand. After much research, Zoom meetings, and sharing of his medical and imaging records, I had finally gotten him accepted into a clinic in Tijuana for therapies and procedures for his cancer that are banned in the U.S. There was only one clinical trial for relapsed, chemo-resistant alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. It was at UCLA, and I was working tirelessly to get him into that trial.

Once he started this new chemotherapy, and as the disease progressed in his bone marrow, his blood counts were dropping. He could barely walk, turn over in bed, or get to his urinal. He was weak, shaky, and short of breath. He wanted to go fishing with his dad, and we made it happen for him. He had to be picked up to get into the boat and picked up to get out. It took three days for him to recover from the pain of fishing that day. Sadly, January 7th was the last day he ever went fishing, his favorite thing in the world to do. For the first time since he started chemo, he had to get blood transfusions and eventually platelets as well. Due to the number of tumors in his bone marrow, it wasn’t able to produce enough platelets and RBCs to allow his body to function. His first transfusion was on January 10. At this point, he was losing muscle mass, so Physical Therapy quickly stepped in to try to strengthen his back and legs.

Hospice was steadily increasing his pain medications, and morphine concentrate was added to his regimen. I rotated heating pads, pillows, and would massage the different areas that were hurting him for hours. I eventually got a massage therapist to come to our house to massage him twice a day. His body was having trouble regulating its temperature, and he would soak his sheets 3–4 times a day. He was sleeping with me by this time and needed around-the-clock care. He would cry so much and would want me to hold him in bed. It tore me apart. The transfusions increased, and they no longer got his counts to baseline as they did when they first started. He was ghostly pale, and it was terrifying. I knew I was quickly losing him. Every second, more of him was slipping through my fingers.

Mid-January, he started hallucinating. Reaching in his sleep, doing motions with his arms that resembled previous normal activities (casting his fishing rod, brushing his teeth, tying lures on his rods, drinking from a cup). And he started talking in his sleep, too. So much talking, muttering, and whispering. The whispering was so intense, and I couldn’t understand what he was saying. What was he saying, and who was he talking to?

By this time, we didn’t know day from night. He was requiring care all day and night. Everything was such a blur. He was having conversations with me that weren’t real. At first, I would let him know he was dreaming, but eventually, I just played along. When he woke up and was lucid, he didn’t know if the things he was doing and saying in his dreams were real or not. And he cried. So much crying. He didn’t want me to leave his side and wanted me to hold him even though his body was hurting so much. So, I did as much as I possibly could. His body was struggling more and more to control its temperature. He would be cold one second, then drench himself and me in sweat the next minute. There were more tumors coming up on the bones in his body, especially on his skull. You could see large lumps on his head, at least five to six of them, and they kept growing. It was horrifying to see. There was no doubt that the cancer had entered his brain. His oncologist wanted to do scans to look at the brain, but we refused. No more scans. Both he and I knew what was happening and didn’t want to see it or read it in a report. Plus, we despised people looking at us with pity. An agreement between him and me was that I would never look at him with pity or give up on him. Ever. Also, at that same time, we decided no more chemo. We had medical plans from the Integrative and Naturopathic oncologists that we were following. We just needed more time. The new medical plans would start making a difference eventually. I knew we were racing against time. Please, Lord, give us more time. He would tell me, “Momma, I don’t feel like my story is over yet.” And I would tell him, “Of course it’s not over yet. It will never be over, baby. And I will do everything in my power to make sure of that.” I prayed tirelessly for more time. I had to get that time for the new regimen to work. It would work; it had to.

He had no appetite and seemed not to be digesting anything by mouth. I started crushing the supplements recommended by his Naturopathic Oncologist and putting them through the G-tube, desperately trying to keep him alive. His behavior became what I can only describe as an autistic toddler. He had to have a schedule, know exactly what was happening and when. He needed to know what was expected of him that day, and wanted me to know what his goals were for the day. If we detoured from that, he would have meltdowns. It was painful to see him like this. Some of the goals he had for himself were to focus on being awake and alert for 3–4 hours a day so he could spend time with me, eat a few blueberries and strawberries by mouth for me that day, and encourage me to stop stressing so much. He said he could feel my anxiety, and it was something he couldn’t handle. My goals were for him to try to eat something by mouth that day to keep his esophagus working, let me stretch his legs and arms, and listen to me when I told him we had to do a feed, take meds, drink water, and change sheets. And we both wanted to read as many as possible of the cards and letters of love he was continuously getting in the mail. He didn’t want anyone but me to touch him, help him, or care for him. We did not deviate from these goals, or he would cry so much. I knew this couldn’t continue, but there was only one way it would stop—and that is something I refused to accept.

We were not approved for the clinical trial at UCLA because one of the qualifications was a three-month life expectancy, and due to his extensive disease, they felt he didn’t have that long. Plus, because of his pain, he could barely ride in a car to the hospital, much less a plane ride to California. David and I decided to turn down the Tijuana clinic’s acceptance. The plane ride would be horrific. Additionally, I was the only one who could go with him, and what if he died over there, and I was alone?

On January 27th, he was back in the hospital for another blood transfusion. The cancer in his bone marrow was getting worse, and transfusions were getting more frequent, but didn’t seem to make much of a difference in his counts. With each hospitalization, he wanted me in bed with him, but this time it was different. That evening, in his sleep, he was thrashing around, throwing his arms and fists, trying to pull out his port, and had to have me plus two nurses hold him down for blood pressure checks. And so much muttering and whispering. We were shocked. When he was lucid the next day, he didn’t believe he had behaved that way, but the way his port looked was proof. Hospice was very concerned and came into our hospital room the next morning to talk to me. They strongly suggested I allow them to take him to the Hospice Care Center upon being discharged to get his hallucinations under control in real time. I told them absolutely not. There is no way I’m allowing that to happen. Just give me the meds, and I can do it myself at home. No need to go to the Hospice Care Center. This went on for hours. After much discussion, I finally agreed but made sure they understood we would only be there for two days, then go home once the medication got him stabilized. Will wasn’t happy about the plan and initially pushed back, but trusted my decisions and agreed to go. Especially hearing of his behavior the night before. I made sure everyone understood that we were only going for two days and that was it: get his hallucinations under control, and we are leaving.

To be admitted into the Hospice Care Center, a DNR must be signed. Will gave me permission to sign one, and Hospice assured me I could tear it up when we left to go home from the Care Center. He was transported in the Hospice van so he could lie on a bed instead of having to sit up in my car. When I was packing our things up, getting ready to head to Hospice, the hospital discharge papers were given to me as usual. We had been hospitalized so many times that I usually didn’t look at them, just put them in our luggage. But for some reason, I looked at them this time. He was described as a 19-year-old with End-Stage Rhabdomyosarcoma. End Stage? He wasn’t end-stage. Why did no one understand that he wasn’t there yet? Infuriated me. We still had time. Had anyone said that to him? Had he overheard anyone say that? Oh my goodness, I hoped not. Once we got him on the medications he needed at the Hospice Care Center, we would be coming back home to continue the new naturopathic regimen. No questions asked. Two days and that was it.

Once he arrived at Haven Hospice in Lake City, he was started on pain meds before I could get in the room with him. He asked them to stop until I was let into his room. He was so scared. Once I got to him and he was settled in, I held him, and we cried together. We hated the feeling in that place. We were accustomed to people coming in and out of the room, equipment beeping, sounds from the hallway and nearby rooms, but this place was silent. So silent. Eerily silent. We wanted out. Now. But the pain medicine started settling him down, and he was resting. I told him again: we will leave in two days, which would be Monday, January 30th. We will not be staying. Whatever they said he needed, I could do it at home.

David brought over his pump so I could feed him through his G-tube that night. We would be going home soon, so I needed to keep his feeding going. They weren’t offering him any food or anything to drink, so I had it covered. Afterwards, for the first time ever, some of the feeding came out of his nose. He should be digesting it! What was going on? Did I need to have him sit up more? He usually doesn’t have to sit up! Surely his body isn’t shutting down; it’s not time. There was no way I was going to stop feeding him.

That night, what Hospice called “Sundown Syndrome” started up again—agitated, thrashing, talking, muttering, whispering—and that’s when his medication for the hallucinations was started. It helped him relax almost immediately, but he was completely sedated, which I didn’t like. He couldn’t communicate with me at all. I was demanding to know what they were giving him and why he wasn’t waking up. What was going on? This is not right. This couldn’t be the right dose. He still should be able to communicate, but still get his Sundown Syndrome under control. I was frantic and so confused. That’s when they told me he had 48–72 hours to live. Wait, what? We were not there for him to die, just for hallucination control. Hospice doesn’t get to decide when it’s time. They can’t take that out of our hands. This is ridiculous, absurd. I was worried that he had heard them say this. He could not hear anyone say this. This is something that Will and I would decide, not Hospice. There must have been a mix-up in communication from the hospital to the Care Center. Or did Hospice convince us to come here under false pretenses? I was so confused and losing my mind. This is terrible; we need to get out of here. Even though sedated, he was reaching toward my voice. That night, I laid with him in the Hospice bed and held him. He kept muttering and whispering. Why? What was he trying to tell me? He must have heard what the Hospice nurse said.

On the morning of January 29th, he became somewhat lucid. He was trying to communicate even more, and I could make out some of what he was saying. He was confused about what was happening and started crying to go home. I told him I agreed, and let’s get out of here. I immediately started packing our things. I had said two days, but this is not right; we are going home right now. I let the nurse know that we were going home. I didn’t know how we were going to get him home, but it’s happening. She took me into their supply closet and said no—that I cannot take him home. He was in so much pain, and I couldn’t control it at home. His agitation needed to be controlled at night, too. She told me he was crying because he was scared, and no matter what our plans were, I did not want him to die at home. That I had to listen to her. He only had 48–72 hours to live. Please listen to her. Please. She told me that parents always refuse to accept the fact that their children need to be in Hospice at the end. They can provide comfort and a peaceful death. I was furious and became hysterical. Don’t lump me in with other parents.

I fell to the floor with searing sadness that I had never felt before. I was screaming and crying. No, no, no: this couldn’t actually be happening. This was my child, and he was not going to die here. I had just told him I would take him home. We had to get out of here. She got on the floor with me, grabbed me, and shook me. She told me that I am his mother. To get up, stop acting like this, get myself together, and go tell him whatever he needs to hear to calm him. She told me he trusts everything I tell him, so go in there right now and do what I know I need to do. I have to calm him down, and he can’t go home. Tell him what he needs to hear. So, I did. I lied to my baby and told him that we would only be there for one more day and would go home in the morning. Just relax, go back to sleep, and I would lie with him and hold him. And that’s what I did. I asked him if he trusted my decisions, and he said always. The nurse gave him more medicine, and he fell back asleep. I just kept thinking, what have I done? I knew it was time to tell our family and friends that this was the end. If anyone wanted to come see him, the time was now. I started calling and sending out messages.

The rest of that day was agonizing. His breathing was labored, and he would stop breathing for long periods of time, then suck back in air while throwing his arms up. I laid with him and talked to him. I would pull his arms back down when he would suck in his breath. He was trying to say things and respond to me, but nothing he was saying could be understood. Was he trying to tell me something? What was going on? I kept telling him I was so sorry that I couldn’t understand what he was saying. I didn’t understand—if he was about to die, then why was he still trying to communicate with me? That night, if I got up, he would reach for me in the air until I got back in bed beside him. It was harder and harder to get him to relax. The doses of medications to keep him calm and sedated were very high, and despite the increases, they weren’t working like they should have been. The nurse told me I had to get out of his bed, even if he continued reaching for me. They felt that he could not get fully sedated because he was responding to my voice. They wanted me to sit in the chair beside him, hold his hand, and keep my voice to a whisper. Heartbroken, I did, and they were right. The nurse was able to get him to settle down with half the dose he was previously getting. From that moment on, I knew it was over. Truly, this was the end, and I had to accept that.

That Monday, January 30th, his breathing became worse, the catheter bag started filling with blood as his kidneys were shutting down, and the death rattle started. The nurse assured me I could whisper to him, and he could hear me. I had to stay calm because he would pick up on the anxiety and terror I was feeling and react to it. That day, so many family members and friends came and visited him. So much love and heartache in that room that day. He never woke up. I whispered how sorry I was for what had happened to him. So sorry for his pain. So sorry for bringing him to Hospice. So sorry for not letting him decide when enough was enough. Telling him over and over and over that I had no idea we were bringing him there to die. I promise I didn’t know. I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry I didn’t take you home. That I didn’t give up on him. I promise. I had no idea we were coming here to die.

That night, after everyone had left, his breathing was horrific. Stopping, starting, rattling, sucking in. I was talking to his nurse, and she said that with younger patients, their hearts are strong. Even though their bodies shut down and were ready to die, their hearts aren’t. Sometimes this could go on for weeks. What? I was shocked. This absolutely could not go on for weeks. I knew that. He could not stay in this state for weeks. I was so tired, defeated, angry, terrified, and heartbroken. That night, my prayers to God and whispers to Will changed. I had to accept the fact that there was no miracle coming to save him, and there was nothing I could do to change that. No matter how much over the last 13 months I had screamed, pleaded, and cried out for God to step in. It was over. It was time for him to let go.

The night of January 30th, I started praying for God to please take him. Something I thought I would never do. I had to start telling my precious son that it was time to let go. I told him, "Don’t be scared. I will be fine. We would all be fine. It was time to let go. I’m so sorry. I love you so much." I assured him that this was not the end of his story, and he would live on in the ways I would help and inspire others in his name. That I would always say his name. I would always tell his stories. I promise. But right now, it was time to let go. I love you so much. I’m so sorry this happened to you. Don’t be scared. I would be okay. I said this all night. I held his hand, kissed his forehead, and laid my head on his chest. I knew very soon that I would no longer have his body here to touch and comfort.

January 31st, 2023, at 7 a.m., Will passed away. Once again, he stopped breathing, then he sucked in a huge breath, but it sounded different this time. And then it stopped. No more breaths. He was gone. This fight was over for him. There was a calm peace in the room that I will never be able to fully describe. David felt it too, and it’s something that we talk about often. The peace that we felt was palpable. I knew that was God. I knew that God was there, taking his sweet soul from his broken body. Peace that surpasses all understanding.

Together, We Can Create Change.

Your donation helps fuel the search for better treatments and lasting cures for Alveolar Rhabdomyosarcoma. It supports critical research, raises awareness, and gives families facing this rare cancer the support they urgently need. Every dollar brings us one step closer to change.